Britain has been warned that it faces the worst squeeze on spending since the 1970s, when inflation soared over 25 per cent and unemployment rose relentlessly.

Five decades ago, the country was thrust into unprecedented economic chaos by surging oil prices and a global recession.

Households were forced to ration heating, drivers queued for fuel at petrol stations and supermarket shelves were bare.

Big squeeze: The Resolution Foundation think-tank has warned the typical household incomes could drop by 4% – the sharpest annual income fall since the turmoil of the mid-1970s

Rubbish piled up in the streets as binmen went on strike and some workers were forced into three- or four-day weeks as their employers struggled.

Last week, the Resolution Foundation warned that inflation could soar to more than 8.4 per cent this spring – the highest since 1982.

The think-tank said this would mean typical household incomes would drop by 4 per cent – the sharpest annual income fall since the turmoil of the mid-1970s.

Money experts today warn that while the cost-of-living crunch is unlikely to be as extreme, it will be a crisis nonetheless.

Next month spells a raft of new tax and bill hikes that will only make life harder for those struggling with rising prices.

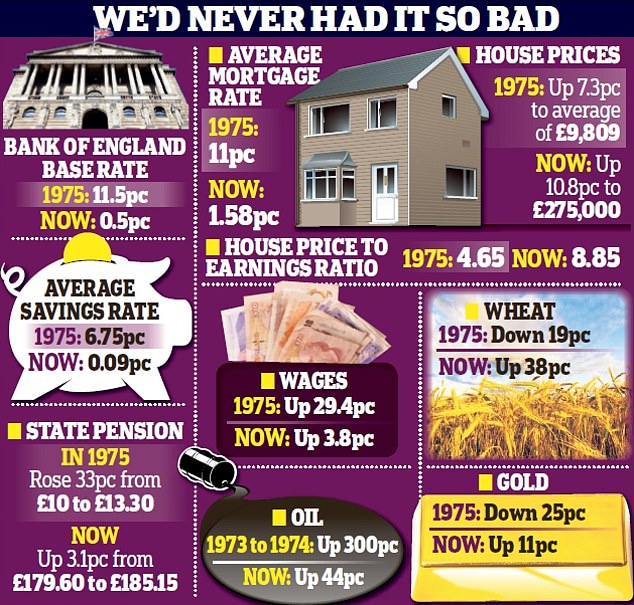

So we crunched the numbers to illustrate just how different things are today compared with nearly 50 years ago when our budgets were last under such severe strain.

Our analysis, by investment firm Hargreaves Lansdown, reveals how the price of a pint of milk rose 80 per cent in 1975 to hit 9p and the cost of a dozen eggs soared 32 per cent to 41p.

Today’s food prices have been modest in comparison, with milk up just 8.5 per cent to 46p and eggs up 8 per cent to £1.80.

Yet petrol prices have already rocketed 24 per cent to £1.57 per litre this year, compared to a rise of just 6 per cent to 16.5p per litre in 1975.

Energy bills are also about to surge by 54 per cent to an average of £1,971 a year, while nearly 50 years ago they rose by 21 per cent.

Today’s food price rises have been modest in comparison with the 1970s, with milk up just 8.5 per cent to 46p and eggs up 8 per cent to £1.80

Noticeably, today’s state pension is not rising to keep up with the cost of living. Inflation hit 22.6 per cent in 1975 and the state pension rose 33 per cent from £10 to £13.30 in response.

Yet now, the new state pension is increasing by just 3.1 per cent from £179.60 to £185.15 a week. Inflation is currently running at 5.5 per cent and could hit eight or even 10 per cent this year.

Jan Shortt, general secretary of the National Pensioners Convention, says: ‘There is a depressing sense of deja vu about today’s cost-of-living crisis for those of us old enough to have lived through the economic turmoil of the 1970s.

‘The parallels are frighteningly familiar — record inflation, rising costs and the poorest and most vulnerable suffering most as they struggle to choose between eating and heating their homes in the midst of a bitter winter.’

Back in 1975, the Bank of England’s base rate also hit 11.5 per cent, whereas today’s rate is just 0.5 per cent.

The average mortgage rate was 11 per cent, yet now it is 1.58 per cent. The typical savings account also paid 6.75 per cent.

Now, savers can get just 0.09 per cent on average. And while inflation soared to more than 22 per cent in 1975, wages also rose 29.4 per cent. Earnings have risen just 3.8 per cent over the past 12 months.

House prices rose 7.3 per cent, bringing the average to £9,809 in the mid-70s, whereas they have risen 10.8 per cent in the past 12 months, with the average now £275,000.

They were also around 4.65 times the average wage in 1975, whereas now properties are 8.85 times the typical salary.

House prices rose 7.3 per cent, bringing the average to £9,809 in the mid-70s, whereas they have risen 10.8 per cent in the past 12 months, with the average now £275,000

Sarah Coles, senior personal finance analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown, says: ‘Inflation is not yet at the kind of levels we saw in the 1970s, but coming on the back of decades of low inflation, it has come as a horrible shock.’

Yet pensioners back in the 1970s were more likely to have better private pensions that were linked to salary pay and rose in line with inflation every year, she says.

Ms Coles adds: ‘One similarity to the 1970s is the rise in the cost of essentials like energy and petrol and because those are vital to so many people heating, eating and working, it will hit hard.

‘It’s particularly going to affect those on lower incomes, for whom these things make up a bigger percentage of their monthly spend.

Warning: Former pensions minister Baroness Altmann

‘Another thing to consider is how working life has changed since the 1970s. The trade unions had a great deal more power in wage negotiations, which meant huge price rises were followed by wage increases. It remains to be seen whether market forces will do the same job this time round.’

But Baroness Altmann, a former pensions minister, says households are perhaps now less able to handle such a blow to their budgets.

She says: ‘The shocking thing is that it has happened in such a short time, there has been no warning of it. The difference might be that a lot of people are already in debt.

‘The poorer members of society were not necessarily able to rebuild savings in the pandemic.

‘In the 1970s, the higher savings ratio will have meant people had more reserves to call on. We have record levels of household debt already. This is just going to add to that.’

In the 1970s, the higher savings ratio will have meant people had more reserves to call on. We have record levels of household debt already

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has sent the price of commodities soaring in 2022. But our analysis shows that while gold has risen 11 per cent this year, it fell 25 per cent in 1975.

The price of wheat has also risen 38 per cent this year, but fell 19 per cent in the mid-1970s.

The decade drew to an end with the Winter of Discontent from November 1978 to February 1979, when the country was frozen by strikes against inadequate public sector pay rises.

And when Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in May 1979, her Conservative Government increased interest rates to tame inflation.

The move saw many people lose their homes to record mortgage rates and unemployment also hit new highs.

When Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in May 1979, her Conservative Government increased interest rates to tame inflation.

Now, with Chancellor Rishi Sunak to outline the Government’s spring spending review next week, ministers are facing renewed pressure to help those with low, fixed incomes through the crisis.

Ms Shortt adds: ‘Pensions barely cover living costs as it is, and they just don’t cover outgoings caused by rising inflation.

Britain has stepped out of a pandemic and straight into a cost-of-living crisis

Adam Corlett, Resolution Foundation

‘Unless the Government acts to help the oldest and poorest survive the perfect economic storm playing out here, it will be the millions of us who weathered the 1970s who will suffer most.’

Adam Corlett, principal economist at the Resolution Foundation, says: ‘Britain has stepped out of a pandemic and straight into a cost-of-living crisis.

‘The immediate priority should be for the Chancellor to revisit benefits uprating in his upcoming Spring Statement.’

Caroline Abrahams, charity director at Age UK, adds: ‘The scale of the imminent energy bill hikes is terrifying for older people.

The Chancellor must do more to protect the most vulnerable older people and give them the confidence to heat and light their homes.’

Strikes, hikes and era of 15% mortgages

By City Editor ALEX BRUMMER

The 1970s were the best and worst of times of my life.

It was the decade of my debut in financial journalism, of my marriage and first tentative steps up the ladder of the home-owning democracy.

But also a time of economic devastation when lives were blighted by surging levels of inflation, banking collapses, incessant strikes and — as the icing on the cake — a brutal IRA bombing campaign.

The origins of the great inflation of the 1970s were not very different to what is happening in the UK and across the world today.

Cars queue for petrol at Cromwell Filling station on the Cromwell Road in 1973

The Yom Kippur war between Israel and its Arab neighbours in 1973 saw the Strait of Hormuz blockaded and the price of petrol at the pumps, and domestic and business energy bills, soar.

Easy credit offered by the Bank of England meant that there was loads of cash chasing too few goods.

Add to this widespread industrial action in demand of double-digit wage rises, blocking coal production and leaving coke imports piling up at the ports, and the inflation crisis also became an energy catastrophe.

Today, we often hear talk of the lights going out. In the 1970s, we experienced the three-day week (when we were forced to cease production) and regular brownouts when the lights dimmed. There was no point in turning up the thermostat because the heat simply didn’t come on.

As a first-time house buyer, the problem wasn’t just the volatile cost of a mortgage, which bounced up and down with changes in the Bank of England’s bank rate, but getting a loan at all.

Fixed mortgage rates — which provide a degree of certainty for the home buyer — were unknown, so what began as an 11 per cent mortgage, at one point reached an eye-watering 15 per cent.

Getting a home loan required the borrower to have a long-term relationship with the building society, in the shape of a deposit, before the manager would even let you through the door for a gruelling interview.

Yes, houses appeared to be much more affordable, but when the bank rate skyrocketed it was a case for many of us of the ‘whole’ pay cheque being swallowed.

Escaping the endless strikes, rubbish piling up on the streets and shop prices rising by the day was never an easy option.

The pound was in perpetual retreat on the foreign exchange markets until Britain was bailed out by the International Monetary Fund and the U.S. in 1976.

That meant the cost of imported goods, from pasta to Jaffa oranges (considered a luxury at the time) were in perpetual upward motion.

For those of us wishing to travel abroad, the maximum amount of foreign currency one could take on a trip was confined to £50 only.

Hence, the rise of the all-inclusive package tour industry. Amid all of this chaos, as an economics writer there was one saving grace.

I knew that each rise in the inflation rate meant that the debt built up, in the shape of a mortgage and what seemed at the time like a whopping overdraft of more than £1,000, was shrinking in size in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

More importantly, perhaps, London was a city under siege with a savage IRA bombing campaign.

Lives were lost in the City of London when a device detonated at Cannon Street train station close to where I worked.

That put double-digit inflation, disruptive strikes and money troubles in some perspective.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.