Since the late 19th century, sauropod dinosaurs (long-necks like Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus) have been almost universally regarded as herbivores, or plant eaters.

However, until recently, no direct evidence – in the form of fossilised gut contents – had been found to support this.

I was one of the palaeontologists on a dinosaur dig in outback Queensland, Australia, that unearthed “Judy”: an exceptional sauropod specimen with the fossilised remains of its last meal in its abdomen.

In a new paper published today in Current Biology, we describe these gut contents while also revealing that Judy is the most complete sauropod, and the first with fossilised skin, ever found in Australia.

Remarkably preserved, Judy helps to shed light on the feeding habits of the largest land-living animals of all time.

Plant-eating land behemoths

Sauropod dinosaurs dominated Earth’s landscapes for the entire 130 million years of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Along with many other species, they died out in the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous 66 million years ago.

Ever since the first reasonably complete sauropod skeletons were found in the 1870s, the hypothesis that they were herbivores has rarely been contested. Simply put, it is hard to envisage sauropods eating anything other than plants.

Their relatively simple teeth were not adapted for tearing flesh or crushing bone. Their small brains and ponderous pace would have prevented them from outsmarting or outpacing most potential prey.

And to sustain their huge bodies, sauropods would have had to eat regularly and often, necessitating an abundant and reliable food source – plants.

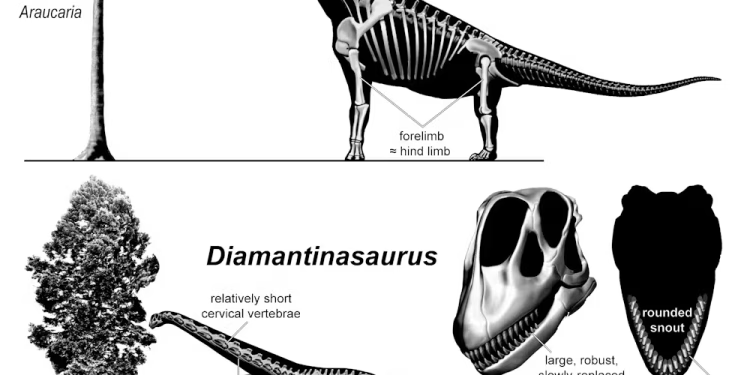

Although the general body plan of sauropods seems pretty uniform – stocky, on all fours, with long necks – these behemoths did vary when we look more closely.

Some had squared-off snouts with tiny, rapidly replaced teeth confined to the front of the mouth. Others had rounded snouts, with much more robust teeth, arranged in a row that extended farther back in the mouth. Neck length varied greatly (with some necks up to 15 metres long), as did neck flexibility. In addition, a few of them had taller shoulders than hips.

Absolute size varied too – some were less enormous than others. All of these factors would have constrained how high above ground each species could feed and which plants they could reach.

Food in the belly

Sauropod discoveries are becoming more regular in outback Queensland, thanks largely to the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton.

In 2017, I helped the museum unearth a roughly 95-million-year-old sauropod, nicknamed Judy after the museum’s co-founder Judy Elliott.

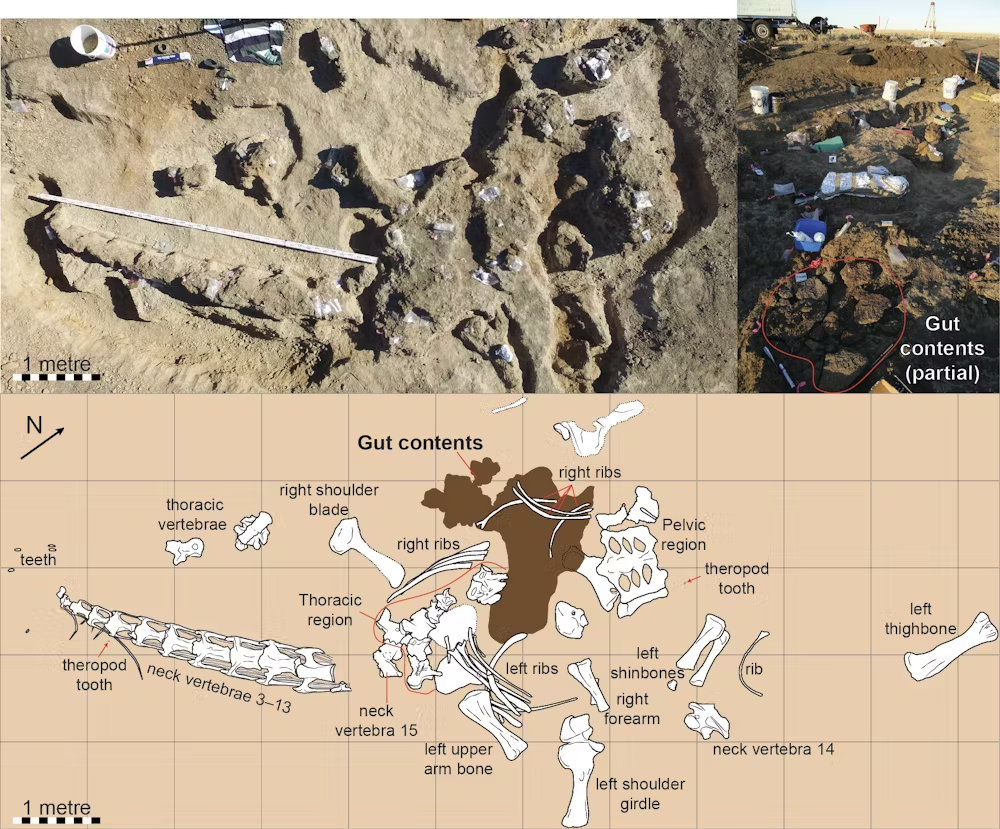

We soon realised this find was extraordinary. Besides being the most complete sauropod skeleton and skin ever found in Australia, Judy’s belly region hosted a strange rock layer. It was about two square metres in area and ten centimetres thick on average, chock-full of fossil plants.

The fact this plant-rich layer was confined to Judy’s abdomen and located on the inside surface of the fossil skin, made us wonder – had we unearthed the remains of Judy’s last meal or meals?

If so, we knew we had something special on our hands: the first sauropod gut contents ever found.

Multi-level feeding

Analysis of Judy’s skeleton, which was prepared out of the surrounding rock by volunteers in the museum’s laboratory, enabled us to classify her as a Diamantinasaurus matildae.

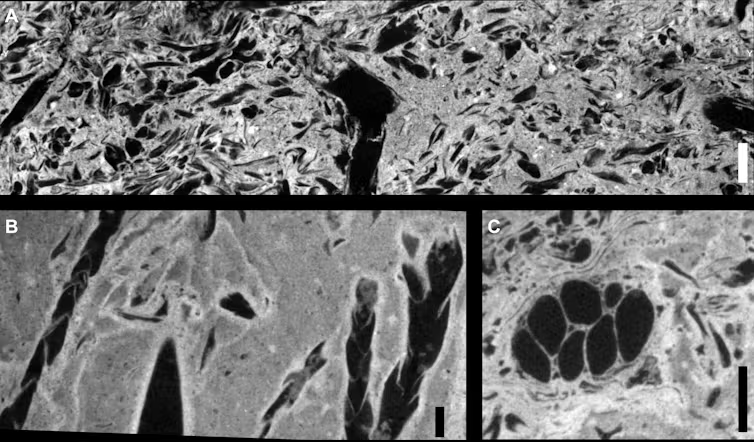

We scanned portions of Judy’s gut contents with X-rays at the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne and at CSIRO in Perth, and with neutrons at Australia’s Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation in Sydney.

This enabled us to digitally visualise the plants – which were preserved as voids within the rock – without destroying them.

We did destructively sample some small portions of the gut contents to figure out their chemical make-up, along with the skin and surrounding rock.

This revealed the gut contents were turned to stone by microbes in an acidic environment (stomach juices, perhaps), with minerals likely derived from the decomposition of Judy’s own body tissues.

Judy’s gut contents confirm that sauropods ate their greens but barely chewed them – their gut flora did most of the digestive work.

Most importantly, we can tell Judy ate bracts from conifers (relatives of modern monkey puzzle trees and redwoods), seed pods from extinct seed ferns, and leaves from angiosperms (flowering plants) just before she died.

Conifers then, as now, would have been huge, implying Judy fed well above ground level. By contrast, flowering plants were mostly low-growing in the mid-Cretaceous.

Based on other specimens (especially teeth), scientists previously thought Diamantinasaurus browsed plants relatively high off the ground. The conifer bracts in Judy’s belly support this.

However, Judy was not fully grown when she died, and the angiosperms in her belly imply lower-level feeding, as well. It seems likely, then, that the diets of some sauropods changed slightly as they grew. Nevertheless, they were life-long vegetarians.

Judy’s skin and gut contents are now on display at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton. I’m not sure how I’d feel about having the remains of my last meal publicly exhibited for all to see posthumously, but if it helped the cause of science, I think I’d be OK with it.![]()

Stephen Poropat, Research Associate, School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.